When I think about it, I was introduced to politics via the 1995 Québec referendum. I was a sniffly, hypersensitive bilingual fifth-grader attending a snooty multi-cultural private French grade school. From what I could tell, most of us 10-year-olds didn’t much fancy the idea of a sovereign Québec. Who knows why? Being 10, our political analysis probably wasn’t too sophisticated. My reason was simple: a free Québec meant that my mom and I would likely leave this place I called home. That we’d move far away from my Papa Luc. And that’s all the reason I needed for wanting Québec and Canada to hang on just a little while longer.

One of my classmates happened to be the grandson of Québec premier and sovereignist figurehead Jacques Parizeau. He was a nice kid. Shy. A tad cocky. But when his grandfather got on stage that brisk October night, seemingly drunk and bitter off defeat and blaming big money and immigrants for refusing him his country, you best believe that the stage was set for my classmate to get mercilessly teased by the big money kids and the immigrant kids who made up his cohort. There was even an intervention featuring all the senior administrators telling us to stop picking on him, as he was not responsible for his grandfather’s slurred words. Tense, to say the least.

A friend of mine recently told me how her family was too afraid to hang a Canadian flag up on their balcony in a predominantly English Montréal neighbourhood during the referendum. Others have shared memories of being chased out of roadside diners for speaking French outside of Québec during family holidays.

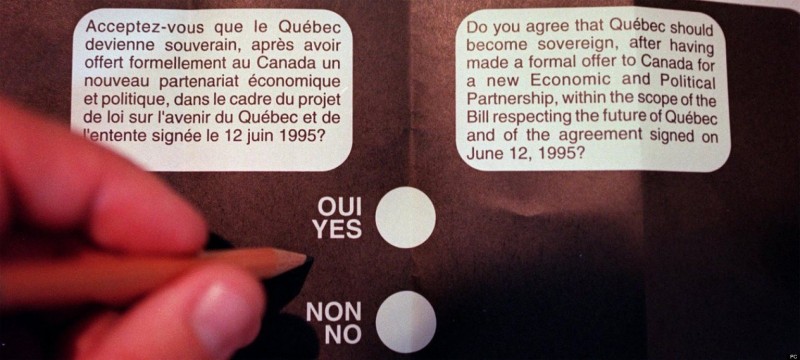

I get the impression that none of us in Québec reminisce about those months 19 years ago with much fondness. Cheerful memories and le référendum don’t go hand-in-hand. But nobody ever said this kind of democracy was easy. It’s not simply checking a name next to a box of whom you want to “represent” you. It’s deciding, quite literally, on the fate of nations.

It’s no afternoon stroll in the park. It’s reflection. It’s arguing. It’s work.

Given the heavy emotional, spiritual and physical toll these moments can take on a people, it’s reasonable to allow some time before going through the exercise all over again, if at all. Wait it out a bit and see where people’s heads are at. And 19 years later, support for sovereignty routinely wavers between 30 to 40%. That’s 3 to 4 people out of 10 who want Québec’s independence. That’s upwards of 2.5 million people saying qu’ils veulent un pays.

Is it so unreasonable to consider asking that question again? Should we not, as a people, relish in the opportunity to be truly consulted on something once and a while? Do we even realise how long ago 1995 was?

In 1995, the #1 songs were Céline Dion’s “Pour que tu m’aimes encore” and Coolio’s “Gangster Paradise“. In 1995, La Petite Vie was shattering Québec television records. In 1995, Québec City still had its Nordiques. In 1995, the average household computer had a whoppin’ 8MB of Ram and included a game-changing operating system by the name of Windows ‘95. In 1995, there were no MP3 players. In 1995, Forest Gump was teaching us about life and chocolate.

In 1995, Robert Bourassa, Pierre-Eliott Trudeau, Maurice Richard, Dédé Fortin, Pierre Peladeau and Marie Soleil-Tougas were still alive, free to vote.

In 1995, revolutionary bad-boy extraordinaire Gabriel Nadeau Dubois was in kindergarden. Léo Bureau-Blouin was 4. Martine Desjardins was a granny at 14. Over a third of the Québec caucus of the federal NDP were trading PB&Js in the hallways. Even popular Montréal ex-mayoral candidate Mélanie Joly was too young to cast her vote on the future of Québec.

In last month’s election, 26.64% of registered voters were born after 1978 and thus were too young to vote the last time Québec reflected on la question nationale. That’s over 1.5 million eligible Québec voters who have never even been asked the question.

Yet, we continue to treat every election as if it were a referendum on a referendum. We continue to be so fearful of being asked a question that we are willing to forego all other issues.

This isn’t good for our personal or our collective health, Québec, and it needs to stop. Sometimes, we need to have these hard conversations. Sometimes, we need to be ready to put our minds together to envision how we want our communities to evolve. Sometimes, we need to conquer bad memories and try talking once more. These once-in-a-generation consultations are needed to find a little bit of peace, however ephemeral it may be. Without them, or rather with the continued instance to reject and demonize them no matter the cost, we’ll be forever stuck in a vicious spiral of fear, hatred and paranoia. Without them, we’ll grow old, bitter, and frankly, lifeless.